After retired state Sen. Frank Madla and members of his family died in a fire in November 2006, the tragedy raised an obvious question: Are San Antonio firefighters doing a good job arriving to fires quickly and keeping residents safe? Express-News Projects Editor David Sheppard asked us to find out.

At this point, what would you do to get the story? Maybe call the Fire Department and ask them for quotes and statistics? Talk to homeowners to get anecdotal evidence?

Related: Telling stories with data: Police chases and drug smugglers on the Texas-Mexico border

In the old days, those were the methods journalists were stuck with. We wouldn’t be able to write anything beyond a superficial story. We wouldn’t truly understand the scope of the problem.

Data journalism

The rise of the computer age has helped reporters take the initiative to do their own analysis of public records. Journalists are analyzing government data to come up with their own findings and discoveries. It takes time and patience. But these new reporting techniques are uncovering compelling stories that are a public service and can’t be found anywhere else.

The rise of the computer age has helped reporters take the initiative to do their own analysis of public records. Journalists are analyzing government data to come up with their own findings and discoveries. It takes time and patience. But these new reporting techniques are uncovering compelling stories that are a public service and can’t be found anywhere else.

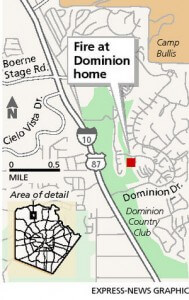

For the fire story, we asked the city for a copy of its entire database of incidents documenting responses to structure fires in San Antonio. The database showed the location of each fire and how long it took firefighters to arrive.

With the help of Express-News Database Researcher Kelly Guckian, we plugged the incidents and response times into a citywide map. Here’s part of the story I wrote with Guckian and Reporter Karisa King:

City records show the Fire Department’s mission of protecting lives and property is clashing with San Antonio’s appetite for new land.

In the past six years, firefighters rushed to inner-city blazes far more quickly than to fires in popular outlying areas that attract thousands of new homeowners.

Delays on the city’s edges plague rich and poor alike, from the exclusive enclave of the Dominion to low-income neighborhoods like Sunrise, a struggling community on the far East Side.

San Antonio annexed many of these neighborhoods despite protests by residents, who complained the city would fail to provide swift fire protection.

The city’s own records reveal that most of the time, those fears came true.

A powerful tool

The analysis of the data took the story in whole new directions. When we sat down with fire officials to interview them, we didn’t have to start out by asking, Is there a problem with response times in San Antonio?

The analysis of the data took the story in whole new directions. When we sat down with fire officials to interview them, we didn’t have to start out by asking, Is there a problem with response times in San Antonio?

We already knew there was a problem. We showed them copies of our maps, told them what we found out from their database, and asked them, Why are firefighters taking so long to reach fires on the outskirts of the city? It changed the entire dynamic of the interview.

Many newspaper critics complain that reporters don’t simply “report the facts.” Maybe these critics would have a problem with journalists taking the initiative to conduct their own analysis of public data.

I would counter that our job is to tell readers what’s really going on. And by making sense of public data and asking our own questions, we are finding stories that help readers make sense of a complicated world.

At a time when newspapers are struggling, these kinds of public-service stories might save them.